These are the words of the famous Soviet song, based on a poem by Yevgeny Yevtushenko. The poet said the idea of writing such a poem occurred to him in the fall of 1961 during his trip abroad because he repeatedly had to hear the same question: “Do the Russians want war?” Today, this question sounds relevant again. Russian sociologist Denis Volkov, head of the Levada-Center, has made the most comprehensive, in my opinion, attempt to answer it, based on surveys and interviews. I base my essay on his article with the author’s permission.

When asked in what areas the situation in 2021 deteriorated the most, Russians ranked relations between Russia and the West/NATO first (56%), which was one of the highest values of this indicator in the history of polls—it was higher only in 2014. That year, Russia annexed the Ukrainian peninsula Crimea and sponsored a military conflict in the eastern part of Ukraine, Donbas.

A significant share of Russians believe that the war between Russia and the West has long been going on, even if it is invisible, cold, and informational—an opinion that has been heard in focus groups in different parts of the country for many years. This confrontation is unfolding in other countries: Georgia, Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Syria, in the EU. Russian participation in recent international conflicts has been perceived by Russian public opinion almost exclusively through the prism of geopolitical confrontation with the West, primarily with the United States.

About half of Russians (53%) do not believe in a war between Russia and Ukraine. However, a comparable number of people—39%—hold the opposite opinion (the sum of “it is inevitable” and “it is quite possible”). Only 15% exclude the possibility of such a conflict entirely.

The Kremlin propaganda machine has successfully pushed its narratives into the public consciousness. Most Russians in surveys and interviews say they share the concerns voiced by the authorities, that they see a threat to Russia from the West, while at the same time seeing no threats to other countries from Russia.

Most Russians blame the United States and NATO for the current escalation: Half in the surveys held this view. Only 3%-4% say the Russian leadership is responsible, which can be considered a marginal position. And this structure of assessments of what is happening is quite stable: “U.S. and Western interference in the internal affairs of other countries” has long since become a universal explanation of any foreign policy situations for a noticeable part of Russian society: From the conflict in Syria to the recent war in Karabakh or the crisis on the Belarusian-Polish border. No matter what happens in the world, America is to blame.

In focus groups, respondents say that the U.S. and the West are solely responsible for the aggravation of the situation and deliberately and purposefully provoke Russia, wanting to drag it into war. “America and Britain are pushing Ukraine to aggressive actions in Donbas, and by this, they are trying to force Russia to stand up for Russian citizens who live on the territory of Donbas; and this will be a reason for further sanctions”; “We are being provoked on purpose, to impose sanctions, so that the economy will be worse again.”

NATO’s military activity near Russia’s borders proved to a significant number of discussion participants that they could not trust Western accusations against Russia: “After all, NATO is expanding to the East. You must agree that there are American planes and ships in the Black Sea, they are all pulling up, and there is an expansion to the East, to Ukraine”; “American ships in the Black Sea, and we tolerate all this! We must be more decisive; these are our borders, our territory. We want to, and we will, bring troops to the borders; we will hold exercises there.”

At the same time, most Russians do not trust the regularly appearing publications in the Western media about the pulling of Russian armed forces to the Ukrainian border and Russia’s readiness to attack Ukraine. Focus group participants argue that Russia cannot have any goals in a hypothetical war with Ukraine, and that the fears of new aggression expressed in the West are unsubstantiated.

The Kremlin has chosen the security issue as the “main line of attack” in the information war with the West and has concentrated its efforts on it. The West does not respond substantively to Russia’s fears. At the same time, its “attacking efforts” are scattered in multiple directions—Nord Stream-2, the Belarusian border crisis, constant threats of new sanctions, and criticism of Russian military aid to Kazakhstan. As a result, steady “information noise” has emerged for the average Russian, in which individual notes cannot be heard. The flow of poorly discernible “negativity coming from the West” is nothing but irritation for the absolute majority. They do not want to hear and understand the messages coming from the West.

The results of surveys and focus group materials reveal that Russian public opinion about Ukraine’s events is highly homogeneous. The available data do not show the usual distinctions based on the age of the respondents or the sources of information used. Over the past few years, Russian youth, viewers of video blogs and readers of Telegram channels, on the one hand, and representatives of the older generation, who prefer television, on the other, have differed markedly in their assessments of the government, the political situation, the most important political events, and attitudes toward the protests in Russia and Belarus. The former was more oppositional, while the latter demonstrated loyalty.

However, on the Ukrainian issue, in their assessments of Russia and Western countries’ actions and their views about the perpetrators of the escalation, both show extraordinary unanimity, up to the use of the same words and phrases used to describe the situation. Unless one knows in advance who is speaking, the statements of young and old Russians on these issues are virtually indistinguishable.

The apparent unanimity can partially be explained by the fact that, for all the awareness of what is happening around Ukraine, this topic is not of genuine interest and is imposed on respondents by the mainstream media. Research participants often speak about fatigue from the Ukrainian topic, foreign policy in general, and confrontation with the West. They have no desire to understand the details of what is happening, to search for alternative assessments, and to double-check the words of officials and TV show hosts.

It turns out that the dominance of the Ukrainian topic on the information agenda has led to “memory overload,” and the issue of Ukraine and relations with the West does not raise attention. Alternative channels for receiving and interpreting information about what is happening have been neutralized.

Most Russian citizens blame the West for the current escalation, almost entirely absolving their own country’s leadership of responsibility. At the same time, there is no mobilization of public opinion around Russian leaders. In the past two months, when the topic of the conflict and new sanctions has been mainly actively discussed, ratings of the President, Prime Minister, and government have not increased. Confrontation with the West has become routine and does not arouse much emotion, despite the harsh statements of politicians.

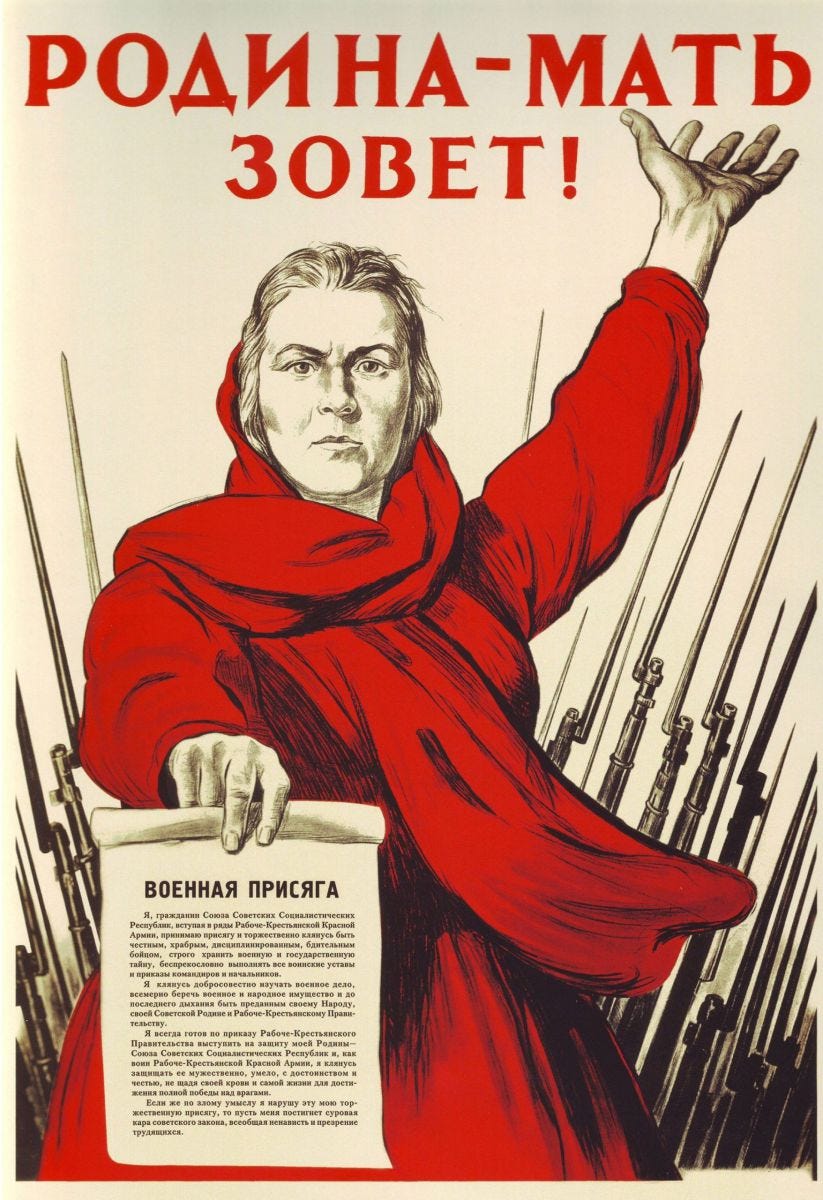

At the same time, if we look at the whole complex of Russian perceptions of a possible conflict with Ukraine and the West…then, although Russian society fears such a conflict, it is prepared for it in its mind. Under the existing perceptions, the war seems to be externally imposed and practically inevitable. This means that in the event of an actual military conflict, the mobilization of public opinion is sure to take place. Russians are ready to perceive a future military conflict because of aggression of the West, and it will cause them to increase patriotic sentiments and a desire to unite “to defend the Motherland”.

Putin is winning the battle for hearts and minds …