May 14, 2022

New ultimatum

Optimistic. As requested

…and his soldiers

Ongoing collapse

**it happens

Purchasing everything

No spare parts soon

The next issue will appear on May 10

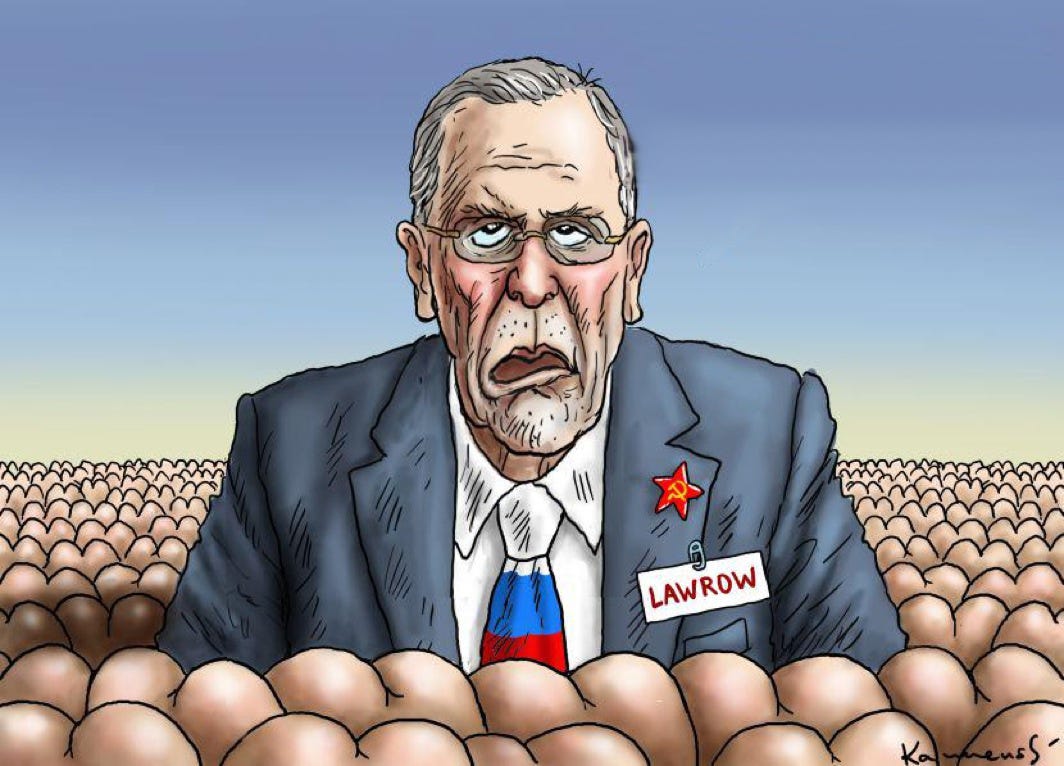

New ultimatum

Although the Russian military cannot report victory in Ukraine to the Russian President, and Vladimir Putin himself complained in a telephone conversation with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz that negotiations between Russia and Ukraine are “essentially blocked by Kyiv,” the Russian Foreign Ministry is expanding its set of demands for Ukraine.

On May 12, the First Deputy Permanent Representative of Russia to the United Nations, Dmitry Polyansky, said that one of Russia’s demands in talks with Ukraine is non-aligned status, which means Kyiv refuses to join any military alliances and organizations, including the European Union.

Previously, we were not very worried about Ukraine joining the EU. But the situation changed after Mr. Borrell’s statement that ‘this war must be won on the battlefield.’ And after the EU became the leader in supplying weapons to Ukraine. I think our position regarding the EU now is more like our position on NATO. We don’t see much difference between the two.

The next day, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov echoed this position.

… the innocuousness of such a desire on Kyiv’s part [to become a member of the European Union] raises serious doubts... The EU has turned from a constructive economic platform, as it was created, into an aggressive, militant player, which is already declaring its ambitions far beyond the European continent.

Optimistic. As requested

The Bank of Russia (CBR) published an updated macroeconomic forecast for 2022-2024, based on the hypothesis that the current sanctions will remain in place and that the Russian economy will continue to be isolated.

The basic version of the forecast looks quite optimistic: The decline of the Russian economy will be sharp but short-term—the bottom will be reached already in the 4th quarter of this year (minus 12.5%-16.5% from the last quarter of 2021). After that, the economy will grow (4%-5.5% in the 4th quarter of 2023 from the end of 2022). “Structural transformation” (a term invented by the CBR)—breaking up existing chains and logistics schemes and building new ones—will continue until the end of 2023, when the Russian economy finds equilibrium at a lower level. Under this scenario, the Russian economy will show growth in 2024 (+2.5%-3.5% by 2023), which, judging by the forecast of the Bank of Russia, will be unsustainable—by the end of 2024, the growth momentum may disappear. Overall, if we follow the average line of the forecast of the CBR, in 2024, the Russian GDP will return to the level of 2013 and will be 7.7% lower than in 2021; the household real income will be 9.6% below 2021. The experts’ optimism looks a bit artificial, related to the Kremlin’s desire to see a trajectory of “confidently overcoming all difficulties”: The report directly states that there are significant risks of a slower adaptation of the economy to new conditions, as well as risks of increased inflationary trends related to the reduction in the supply of goods and services.

There are several apparent strains in the CBR’s forecast, which allow balancing the econometric model to get the desired result. For example, private consumption should decline more slowly than GDP, but its decline will be stretched for two years; the transition of the Russian economy to the growth phase will not require significant investments (after the 16%-20% fall in 2022, investments will hardly grow in 2023, 0.5%-4%).

The most problematic is the hypothesis that the decline of Russian imports in physical terms by 32%-36% will be accompanied by an increase in the unit value of imports by 30%. If the Bank of Russia experts were counting on the fact that Russian companies will be able to find adequate channels to receive the same goods, but with changed logistics, then such an increase in the cost of imports may look adequate. However, businessmen’s forecasts suggest that the main emphasis will be finding suppliers of products from China and India, whose goods are cheaper.

In my opinion, the decision to use the hypothesis of a sharp rise in the cost of imports was taken consciously to avoid answering how and when currency regulation will be loosened. This question is beginning to sound more and more clearly—the dollar exchange rate has rolled back to the February 2020 level, which is 14% lower than the level used to calculate budget revenues for 2022. Today, the dollar exchange rate in Russia, on the one hand, is determined by the supply-and-demand ratio; on the other hand, buying currency in the market is prohibited not only for capital but also for many current operations (payment of dividends on shares, interest on bank loans, coupons on bonds), which dramatically reduces demand. Suppose we add to this the difficulties of importers in building new logistical chains, forcing them to reduce their activity, and the seasonal factor (demand for currency in Russia from early May to early August is permanently reduced). In that case, we can assume that the strengthening of the ruble will continue in the coming weeks. Of course, the CBR can eliminate the factors, working for the strengthening of the ruble by removing a significant part of the currency restrictions. Still, it will be contrary to the Kremlin’s counter-sanctions policy, which is aimed at the maximum possible freezing of the capital of investors from “unfriendly countries” in Russia.

Another option for the Bank of Russia to reduce the pressure on the strengthening of the ruble could be the purchase of foreign currency. Still, it is unlikely that the CBR will decide to take this path until it can find reliable ways to hide its reserves from the eyes of American and European authorities.

…and his soldiers

Under President Putin, many constitutional mechanisms have become imitative. Freedom of speech and assembly have been restricted by law. The separation of powers ceased to work after the Kremlin established its control over the legislature and the judiciary. Russia, which under the constitution is a federation, has become a unitary state in which the regions are deprived of minimal autonomy.

For unknown reasons, the transformation of Russia’s political system has not led to the abandonment of the use of election procedures, which for a long time have not been equal, honest, or fair, the outcome of which is determined not by the voters’ voice, but by what instructions the electoral commission receives.

In late 2004, Vladimir Putin initiated the abolition of direct elections for the governors of the Russian regions, acquiring the right to appoint them into his own hands (in the hands of the President). In late 2011, gubernatorial elections were restored following massive political protests. Still, in doing so, the Kremlin introduced a system of filters that allowed it to cut off undesirable candidates from the elections. Since then, the winner in such elections has almost always been a Kremlin appointee, an incumbent governor—out of more than 150 election campaigns since 2012, only five have seen their rivals win.

Already in 2001, President Putin obtained the right to remove governors from office, and, since 2014, this tool has been used by the Kremlin to replace governors who are undesirable or who might have lost the election. Traditionally, governors whom the Kremlin had decided should make way for a new regional leader sent their resignations to the President in March and April. This allowed Putin to appoint caretakers, who would be given ample time to familiarize themselves with the situation in the region and place their appointees in key positions that would ensure his “victory” in the elections.

This year, because all the Kremlin’s attention was focused on Ukraine, decisions on such resignations were delayed for a long time. But given that this year’s election will be held on September 11, further delay threatened to result in a defeat for Kremlin candidates—the announcement of the start of regional election campaigns is to be made between June 2 and June 12. As a result, within 30 minutes last Tuesday, Russia’s five governors tendered their voluntary resignations, and the Kremlin announced who was to replace them. Three of the governors who resigned had served one five-year term, and two had served two terms.

The principles of Putin’s personnel policy concerning appointing his candidates to the post of the governor are well understood. First of all, he must have minimal ties to the regions to which the candidate is being sent to work: One of the five appointees has experience working in the region where he is to become governor. During his conversation with the Russian President, one of the appointees twice confused the name of the region where Vladimir Putin sent him to work. Second, there are no irreplaceable people, just people who are not replaced. One of the future governors had worked in the presidential administration for less than two years. Another was appointed head of Rosstat only three-and-a-half years ago, having no prior experience as head of an agency or in the statistical services. During his time at Rosstat, Russian statistics have not become more responsive or trustworthy. Still, every revision of the data has made the past of the Russian economy look better than before. Another one, three years ago, moved from business to work for the government of a region that is 1,400 km away from the region to which he is to move.

I do not doubt that each Kremlin candidate can win the election in September. And I am sure that none of them will become an independent politician, supported by the voters—in the Russian political system, the only voter, the Kremlin, judges the quality of an official.

Ongoing collapse

Sales of new cars and LCVs (light commercial vehicles) in Russia in April 2022 decreased by 78.5% compared to the same period last year. They amounted to 32.706 thousand units, said the Association of European Businesses. In four months, car sales in Russia have fallen by 43% to 2021 levels.

The largest car factory in Russia, AvtoVAZ, is located in the Samara region in the city of Togliatti. In the first four months, its sales have fallen harder than its total sales by 50%, and the company’s largest shareholder, French Renault, is close to signing an agreement to sell its stake for 1 ruble. Despite this, Dmitry Azarov, Governor of the Samara region, radiates optimism about the company’s near future. According to him, the reason for this is that the company will be put under “Russian management” by the end of May.

I expect all the formalities to be resolved in May, and the company will be under reliable Russian management.

In addition, Azarov said that the company could solve all the problems with components—or rather, find suppliers who have not yet been able to fulfill their obligations because of the lockdowns in China.

Suppliers have been found, as I said; moreover, all the agreements have been reached and executed, but the lockdown intervened. Unfortunately, the lockdown that was declared in a number of regions of China did not allow for the timely delivery of components. COVID-19 again interferes with the plans of car manufacturers in the country and throughout the world. Unfortunately, this has additionally become a negative factor affecting the company’s activities.

I am waiting with interest for the continuation of this story: AvtoVAZ is one of the largest companies in Russia in the civilian machine-building segment, and its situation is an indicator of the general situation in the economy.

**it happens

The Kremlin’s desire to “give an asymmetrical response” to Western countries sometimes leads to ridiculous situations.

In early April, Gazprom withdrew from Gazprom Germania, the primary seller of Russian gas on international markets, and tried to start a liquidation process for the company. Gazprom Germania had subsidiaries in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, the Czech Republic, Singapore, and other countries. After Gazprom’s decision, the German government took control of Gazprom Germania’s activities to maintain the stability of Russian gas sales on the market.

On May 3, Vladimir Putin signed a decree imposing economic sanctions against foreign companies, instructing the government to approve their list. On May 12, such a list was made public: It included 31 companies associated with Gazprom Germania GmbH and another trader, Gazprom Marketing & Trading Ltd, and Polish EuRoPol GAZ SA. According to the presidential decree and the government’s decision, Russian residents cannot conclude deals with these companies, fulfill their obligations on agreements, or conduct financial operations in their favor, including signed foreign trade contracts.

These decisions compromised the export plans of Gazprom and Novatek. Gazprom buys 2.9 million tons of LNG annually from Novatek, which produces the Yamal LNG complex, to supply LNG to India’s GAIL. In addition, through Gazprom Global LNG, Gazprom sells up to 1 million tons of LNG per year, which it receives from the Sakhalin-2 project. Failure to meet its obligations is fraught with lawsuits for Gazprom, and meeting them would incur the wrath of the Kremlin.

Decide for yourself what is the minimum evil in such a situation.

Purchasing everything

The Russian government expects a significant shortage of radio-electronic and other information and communication equipment due to large-scale sanctions and disruption of deliveries under previously concluded contracts. According to Minister of Digital Development and Communications Maksut Shadaev, this will jeopardize the approved digital transformation plans at the federal and regional levels. And according to the deputy head of one of the departments, Yuri Zarubin, to minimize these risks, his ministry is trying “to purchase all free ‘iron’ that is available in the country as much as possible.”

To facilitate such work, Minister Shadaev suggested the government abandon competitive procedures for the purchase of equipment and remove requirements for its suppliers of service support, as well as abandon support for SMEs because of the failure of the minimum share of procurement (at least 25%) and procure from them “depending on the actual conditions.” However, while making rational (considering the situation) proposals, at the same time, Minister Shadaev did not forget about the need to preserve the flow of corruption: He suggested that regional authorities should give priority to local companies [in practice, companies affiliated with regional officials] when purchasing from a single supplier.

No spare parts soon

Tinkoff Insurance summed up some of the results of its unit in the auto insurance segment: After the war started, auto parts prices went up by an average of 30%.

Body repair parts, the replacement of which has been the most popular in recent months, rose in price at the end of April by an average of 31% over February. Among exterior body parts, bumpers (front and rear) went up in price, regardless of the car brand—by 34% and 32%, respectively. Headlights also rose by 32%; fenders by 31%; front doors by 30%; hoods, rear doors, and grilles by 29%. Glass went up in price least of all, by 26%.

Alexei Gulyaev, Deputy General Manager of the Avilon dealership for service, says that “in general, stocks of components in warehouses are thinned. Available quantities are enough for two to four months of work.” Roman Timashov, Service Director of Avtodom Altufievo, agrees with him: “For relatively old models (five years and older), non-original body parts are available; there are second-hand parts offers. For new and unique models, there is an acute shortage of body parts (from windows and headlights to fenders and bumpers).