September 26, 2022

Should come crawling on their knees

Chaos in drafting

Not everyone is happy

And many want to flee

Run, Kremlin, run!

Gazprom saves investors

No good news for auto

Zero-sum game

Just a fact

Should come crawling on their knees

President Putin’s decision to mobilize was an admission of the failure of the plan for the military operation in Ukraine. It has now become clear that the only goal of this plan is to change the political leadership in the neighboring country, which cannot be achieved without defeating the Ukrainian army. The original plan—a blitzkrieg, the capture of Kyiv, and the elimination of President Zelensky—failed in March; it was replaced by an updated plan focused on military victory in the Donbas, the capture of Zaporizhia and Mykolaiv. However, military action showed that the opposing forces had leveled off by the summer, and the Russian army had practically stopped advancing.

I do not know what “recipe for victory” was offered to Putin by the Russian generals, but apparently they directly informed him that “with such a number of the army, Ukraine cannot be defeated.” In this situation, the Kremlin had a choice of three scenarios: 1) Declaring victory and withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukrainian territory, 2) Formulating the terms of a peace treaty/agreement on an armistice (Minsk-3), stopping hostilities, and starting negotiations mediated by Turkey and the UN, or 3) Escalating the conflict. Recognizing Vladimir Putin’s views and values, it is easy to understand that his administration officials did not even dare to offer him the first alternative. The second scenario was rejected by the Ukrainian authorities, who, after the military success in the Kharkiv region, believed that Ukraine might defeat the invaders. As a result, the unprepared announcement of mobilization and the urgent holding of “referendums” on annexing the occupied territories to Russia.

I emphasize that the nature of the decisions made and the form of their implementation show that they were not prepared in advance but were the Russian dictator’s reaction to public pressure from “hawks” who accused him of indecision and unpreparedness to take the steps necessary to defeat Ukraine.

Chaos in drafting

The announcement of the mobilization came as a surprise to the Ministry of Defense, which oversees the military registration and enlistment offices. Only a day later, the military department was able to formulate the criteria for mobilization—privates under 35, junior officers under 50, senior officers under 55—and send out planning tasks to the regions.

A year ago, in September 2021, the media reported that the Russian Defense Ministry had begun creating a “Combat Army Reserve of the Country” (BARS), offering those who had completed military service to become “professional reservists.” Such people were to maintain their military skills by spending three days a month at military training camps. The size of the BARS could be estimated at 150,000 people. However, it seems that these plans have not been implemented—the mobilization summonses were received by those who did not meet the criteria of the Ministry of Defense or who fell into the category of those who were not allowed to be mobilized. In some regions, military registration and enlistment offices sent out a summons for the traditional military training camps for reservists, which are held regularly in September. The applicants were informed only at the enlistment offices that they were subject to mobilization.

The long-standing problem of military registration in Russia is that the databases, which contain information about the place of residence of a potential conscript, are not updated. According to the law, summonses are to be handed personally against signature. During regular drafts in those regions where the recruitment plan is not fulfilled, the police start mass document checks of men of conscription age, hoping to catch those who can be served with a summons at the police station. This practice instantly spread across Russia after mobilization began, but its effectiveness is unclear.

Although the Russian military says that the mobilization is not urgent, one can say that the Kremlin has set a goal of carrying it out as quickly as possible. Late last week, the heads of many Russian companies received orders from the military registration and enlistment offices to provide lists of workers eligible for mobilization, with their residential addresses. Russian law allows conscription notices to be sent through the companies where they work. Thus, the responsibility for delivering the summonses was transferred to the heads of companies.

Not everyone is happy

The Kremlin’s desire to shorten the mobilization period is understandable: This topic has become central in the public consciousness all over Russia. Although in most regions of the country, mobilization is going smoothly, and Russians uncomplainingly go to the army, in some areas, discontent comes to the surface. The most vigorous protest against mobilization has been in Dagestan, where it has developed into mass rallies and clashes with the police. Dagestan ranks sadly first in terms of the number of people killed in the war in Ukraine—309 residents of the republic are known from official sources to have died.

In Yakutia, the President of the republic, Aysen Nikolayev, stood up for those drafted into the army contrary to the requirements of the law. After his intervention, 120 people returned home. According to Nikolayev, the mobilization, during which 3,300 people are to be taken into the army from the republic, is to end on Thursday this week. It turns out that the share of those wrongly drafted is about 10%.

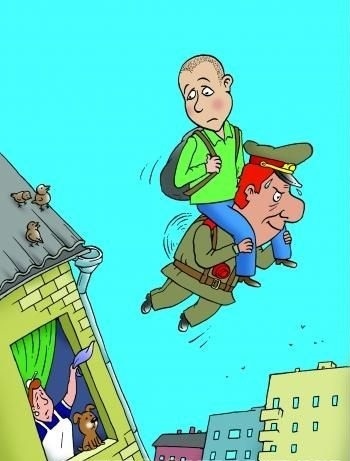

And many want to flee

Meanwhile, those Russians who do not want to lose their lives for the painful fantasies of the Russian President are rapidly leaving the country. At the borders with Finland, Georgia, and Kazakhstan—where it is possible to cross the border on foot or by car—huge lines of those wishing to leave have formed.

At some border checkpoints, FSB officers prohibit the departure of Russians subject to mobilization, sending them to military enlistment offices to “clarify their status.”

Run, Kremlin, run!

Not surprisingly, “referendums” in the occupied territories of Ukraine have been declared valid in three of the four regions. However, procedures will continue until the end of the day on Tuesday, September 27. The Kremlin is determined to complete the annexation procedure quickly, and it is unclear what could prevent this.

Gazprom saves investors

One element of the financial sanctions against Russia was blocking payments by Russian banks and companies to Eurobond holders for coupon and principal payments. From my point of view, this ban was not only senseless but also harmful to the West: The major blow came to bondholders who were not residents of Russia—residents were able to receive payments in Russian rubles.

Perhaps the initiators of this ban were driven by the dream that Russian borrowers would default, which would complicate their access to foreign financial markets for years to come. But the weakness of this position is apparent: After the 1998 financial crisis and after the 2014 wave of sanctions, Russian borrowers were returning to markets where they were welcomed with open arms—Russians were willing to pay higher interest rates, and the stability of their financial situation was not in doubt, as most of them were exporters of raw materials.

Gazprom was the first Russian company to break the financial blockade after the 2014 sanctions. This time too, the gas monopoly decided that its reputation had to be carefully taken care of—no one knows how the future would pan out if Gazprom lost access to the European market. To save its reputation as a reliable borrower, Gazprom exchanged its Eurobonds worth $750 million maturing in 2027, issued under English law and circulated via European clearing and trading systems, for Russian so-called “replacement bonds.” These bonds were issued under Russian law, have the same coupon and circulation term, and are registered in the Russian depository system, after which no Western sanctions will be able to prevent Gazprom from paying the coupon or repaying the principal debt.

The deputy head of the company, Famil Sadygov, said Gazprom intends to complete the replacement of four other issues of its Eurobonds soon. Of the other major Russian borrowers, LUKOIL and Gazprombank announced the issue of substitute bonds.

No good news for auto

The Russian automotive industry suffered the most after the invasion of Ukraine by the Russian army—in May, the production of passenger cars dropped 33 times compared to the previous year. If the statistics are to be believed, the situation improved somewhat in the summer, with the Russian car industry operating at 15% of last year’s level in June to August. This was largely because the flagship company, AvtoVAZ, was able to restore production, having established imports of components from its former shareholder, Renault. It seems, however, that the Russian car industry should not expect good news.

After 15 years of work in Russia, Toyota announced it is ceasing production at its plant near St. Petersburg, where it made 100,000 cars a year of the RAV4 and Camry models. The plant has been idle since early March, and now the company has acknowledged it cannot resume a steady supply of parts from Japan. The company said in a statement that during the six months of forced downtime, it was unable “to develop an approach that would allow a return to full operations” and “does not see any possibility of resuming production shortly.”

At the same time, another Japanese company, Mazda, announced its intention to stop operations in Russia and entered negotiations to sell its stake in the joint venture to its partner, the Russian company Sollers. The plant in Vladivostok began operations in 2012 and produced about 29,000 cars last year.

In October, the Avtotor plant in Kaliningrad will stop producing cars of foreign brands and prepare to launch new projects, said its shareholder, Vladimir Scherbakov:

We will finish the work in early October and ultimately put the production on the changeover. Though not in full swing, we continued to work until the end of September inclusive. Our safety margin was much higher than that of many other plants. It would seem the easiest thing to do would have been to stop us because we have more foreign-made components. And yet, sanctions affected us later than anyone else... further on, we will start implementing a new policy and producing new models adapted to the new conditions of Russia’s development in general and our production inside the country.

In March, Avtotor stopped assembling BMW cars, but the company still had stocks of components for Kia and Hyundai cars. In May, the plant reduced production 4.5 times, from 900 to 200 vehicles per day. The last batch of parts—electronics “with an American trace” stuck, according to Scherbakov, in a European port—the company was able to get in June. At that time, Scherbakov was sure that the plant would be able to continue its work.

We are looking for a solution. We will pick up the remnants in all sorts of ways for a while to get the spare parts we don’t have. I am convinced we will solve this problem even if the Koreans refuse us.

But the optimism was not to be realized. Avtotor started working in 1996 after a group of investors headed by Scherbakov, former deputy chairman of the USSR government, bought a new Nissan assembly plant in Greece, which failed to start up—after Greece joined the European Union and customs duties were removed, the plant could not withstand the competition. The company did not design its cars but focused on assembling foreign brands—the customs benefits for Kaliningrad made this business attractive. The company produced almost 2 million vehicles of 90 models during its operation. The maximum capacity of the plant was 250,000 cars per year.

The closure of the plant will be a severe blow to the economy of the region: Avtotor provided about 40% of taxes collected in the area; transportation of components and finished products loaded more than 55% of sea and rail container transportation capacity; the plant and its allied companies employed more than 30,000 people (the region’s population is 1 million people).

Zero-sum game

No sooner had the Russian steelmakers secured a reduction of the tax burden from the government—the ministers agreed on a higher cutoff price for the calculation of the excise tax on liquid steel—than the Finance Ministry found a way to make up for the lack of budget revenue. The Finance Ministry, in addition to the export duty on coal, proposed to temporarily increase, for January-March 2023, the mining tax rate for coal miners. In both cases, we are talking about an amount of 30 billion rubles, which amounts to 0.1% of the planned expenditures of the federal budget for the following year.

The punctiliousness or pettiness of the RF Ministry of Finance is another reminder that the drafting of the budget for 2023 is complicated. Suppose the Russian Defense Ministry keeps its promise and pays the salaries of the mobilized contract soldiers. In that case, it will cost about 25 billion rubles a month to hold 300,000 people in Russia while there. In the case of those mobilized in military operations, the cost of their maintenance increases by five to six times.

Just a fact

Vladimir Putin gave Russian citizenship to Edward Snowden.