They took us by the throat

On April 28, a citywide pedagogical online event was held in Moscow, where schoolteachers were told how to talk with students about Victory Day and interpret current events in an ideologically correct way. “...we invited all the room teachers to participate. This pedagogical council was organized in more than 500 sites. About 40,000 teachers participated in it,” said Deputy Head of the Department of Education and Science of Moscow, Anton Molev, who led the meeting. According to the teachers, the event was mandatory, and all teachers had to listen to the speeches online from the offices of their school principals.

Lieutenant-General Vladimir Gubernov, the head of the Foreign Intelligence Service (FIS) Academy, spoke before the teachers, telling them how important it was to “correctly present the peacekeeping and liberation character of the special operation” on the eve of May 9 [Victory Day in WWII in Russia] and to remind the children that “behind every conflict after World War II there were certain Anglo-Saxon political interests.”

According to him, the date of May 9 is “a problem point for the whole world and is under attack” because in the middle of the last century, “we were not only against Nazi Germany, but against all Europe, united by Hitler in a three-power pact; now this bloc is called NATO, and its goal is the same—to destroy Russia.”

The part of Gubernov’s speech focused on Poland’s plan to destroy Russia, a project that it had nurtured for “more than a century.” It had already intended to “destroy Soviet Russia from within” in the 20th century.

The main goal was first to tear Ukraine away from Russia. And this is the 1930s of the last century. To achieve a deep enmity between Kyiv and Moscow, up to and including permanent armed conflicts, Russia would have no strength left to oppose the West in the development of Russian riches.

Several teachers tried to ask the questions. One of them asked how a country that suffered such losses in the Great Patriotic War (Russia’s name for WWII) could start a new war in which people died and got a sharp answer.

You just must know the details of what happened. Of course, our country is the most peace-loving, and it is not in our rules and character to start any wars of aggression ourselves. But they took us by the throat; we could not hide our head under the wing.

“How do we not slide into romanticizing war?” another teacher asked. Gubernov replied that we live in a cruel world “where wolves eat bunnies,” so children should be raised “in constant readiness to defend their home,” and should be discarded because it hasn’t saved anyone yet.

This is how the split of the elites looks like

I often encounter the question: What is going on with Russia’s elites? How well do they understand what is happening in Russia and what will happen in the future? On the one hand, total censorship and the threat of criminal punishment for any dissent or criticism of the Russian authorities stop even the most courageous people from answering these questions openly. On the other hand, the people we are talking about here are well integrated into the existing system and are not prepared to go into opposition and/or leave Russia.

However, this does not mean that they unconditionally support Russian aggression and share Putin’s optimism that Russia will cope with all challenges and become more robust due to the “fight with the West.” Below you can read an excerpt from Fyodor Lukyanov’s op-ed in the newspaper Kommersant. He speaks about the radical transformation of the foreign policy situation for Russia and openly accuses the Kremlin of creating obstacles to Russia’s development.

We are used to the fact that foreign policy is the most dynamic and exciting field of activity of the Russian state. I would venture to guess that it will end up in its usual form for Russia for the forthcoming period.

The usual form is the many years of work to bring the country back to a significant position, the restoration of its status to replace the one it lost with the collapse of the Soviet Union. The task had been completed one way or another by the middle of the last decade. Through a combination of different actions, ranging from activities in international institutions and direct contacts with key partners to targeted military operations and economic deals, Russia achieved a prominent place in the world system, although not a leading role. The continuation in the same spirit was supposed to strengthen the position, but without any breakthroughs, fixing the achievements in anticipation of a new stage of global changes.

This now makes no sense. World change has begun, like an avalanche being driven from the top of a mountain. The intensity is such that it is now almost impossible to influence them—not only for Russia, but probably for no one. The cataclysm has largely annulled the accumulated work, and partly still retains significance, but to a lesser extent than before. Russia has no reason to defer to anyone—what is happening is a consequence of our sovereign decisions.

Russia’s “foreign policy” is being replaced by its “international situation”—the surrounding circumstances of which we need to respond quickly and effectively: To adapt, to use, to contain, to prevent. Most of them are long-term and present far more challenges than opportunities in the foreseeable future. The way for our country to influence the world situation is not through diplomacy and other habitual tools of international politics in more or less functional institutions but through the very presence of Russia in the world context. Its reorganization, survival, development, setting and achieving goals, and preserving itself are essential elements of the global landscape. In other words, the fulfillment of tasks that belong to the internal sphere—political and socio-economic. Russia’s place on the political map of the planet depends on this. And not from the drawing of schemes of the world order. Building a country where society and the state trust each other and can create together in an unfavorable environment is the main project of the coming years. We are all aware of how difficult it is to carry out.

Lukyanov is one of Russia’s foremost foreign policy experts, the head of the Valdai Club, at whose meetings he has led several debates with Vladimir Putin, and editor-in-chief of Russia in Global Affairs, where he is also the chief editor of an intensive discussion with representatives of the government. You can’t call him an oppositionist or a dissenter, but he is a thinking and understanding person. And what he said in his article seems to be the maximum degree of freedom of speech in today’s Russia.

Attention is weakening

On April 21-27, the Levada-Center conducted another opinion poll to find out how Russians feel about the situation in Ukraine. The main findings were:

1) Great attention to what is happening in the neighboring country persists, but it is noticeably declining in all age groups except for those aged 35-44;

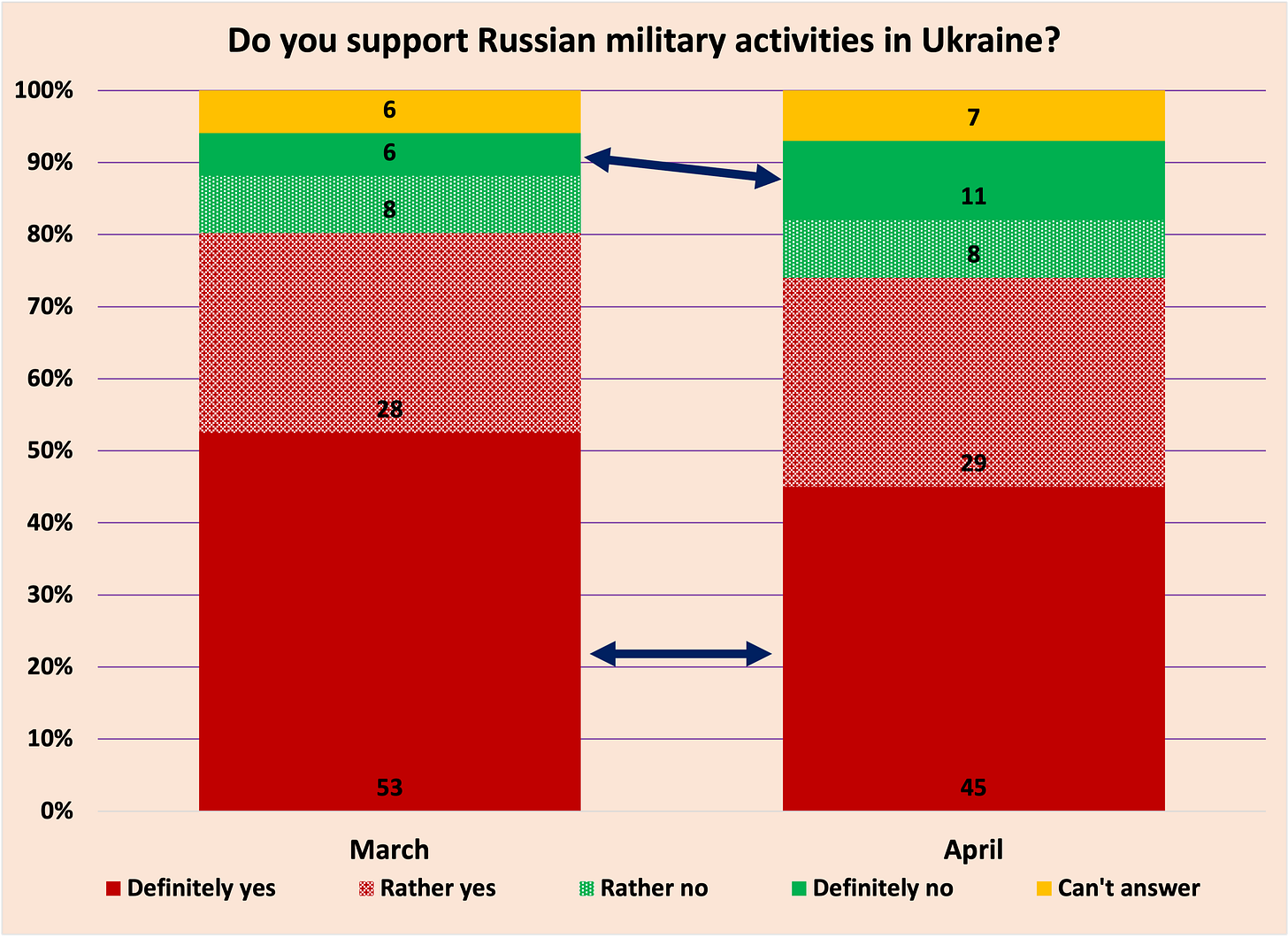

2) Support for the actions of the Russian army remains at a high level; the decrease from 81% to 74% of the total share of those who “definitely support” and instead “support” can hardly be called significant; at the same time, the percentage of those who “definitely do not support” the actions of the Russian military has increased from 6% to 11%. Again, the doubling of the share of such respondents is impressive, but the absolute value of this indicator forces one to temper one’s optimism about possible changes in Russian society;

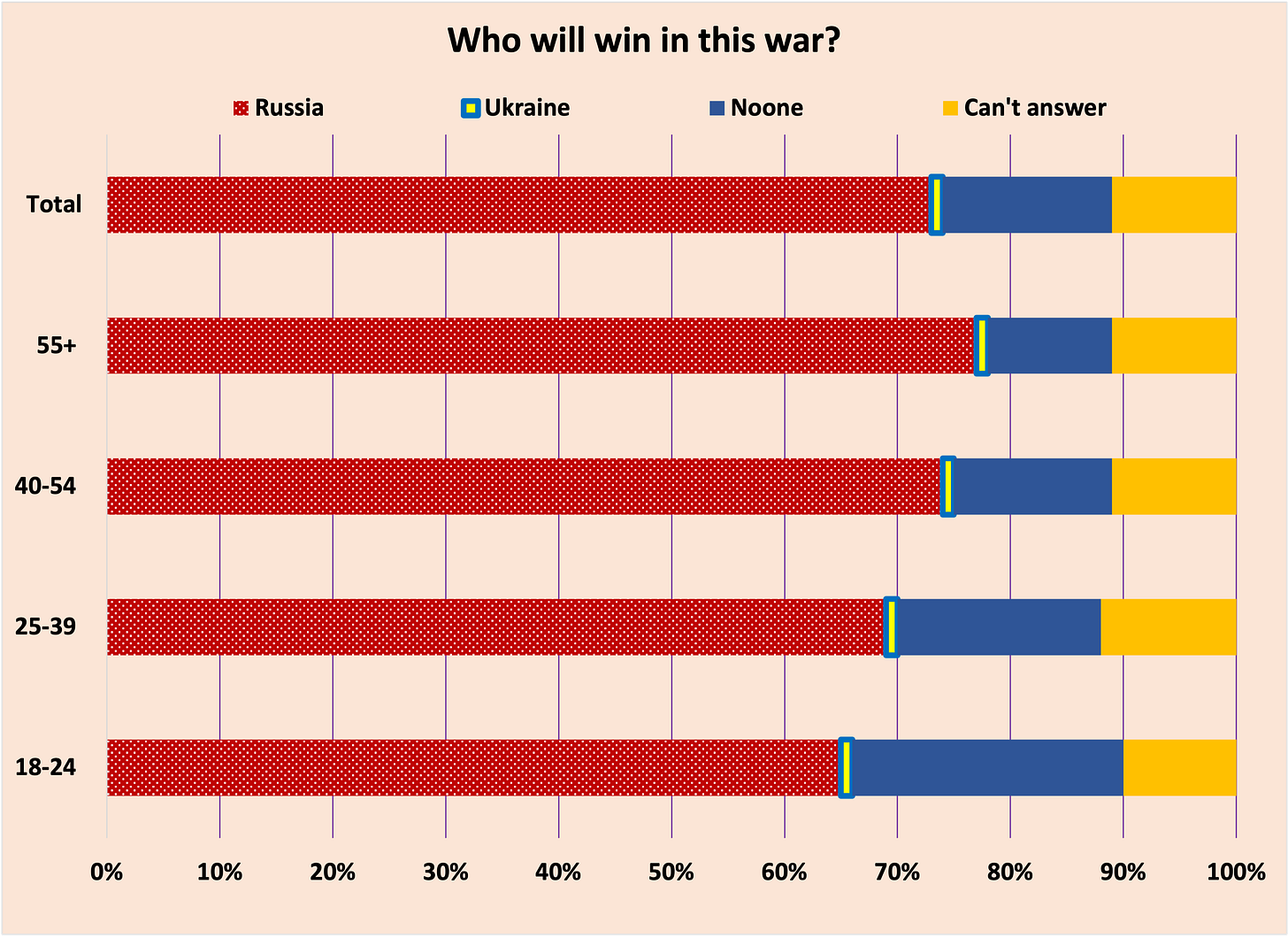

3) The overwhelming majority of respondents (from 65% to 77% in different age groups) have no doubts about the victory of Russia in this war; the triumph of Ukraine seems improbable (only 1% consider it a possible outcome).

Compared to the middle of February, the position of Russians concerning who is responsible for the events in Ukraine (in April, “for the deaths and destruction in Ukraine”) virtually has not changed: It is the USA (60% in February and 57% in April) and Ukraine (14% and 17%, respectively).