Touching a holy thing

March 8, 2022

“Here’s to us, here’s to you, here’s to oil and gas!” is the favorite toast of Finance Ministry employees. And this is no accident: Depending on oil prices, taxes on oil and gas production and exports gave the Russian federal budget between 30% and 50% of its revenues. Exports of oil, oil products, and gas account for 60% to 65% of the value of Russian merchandise exports. Oil and gas revenues have formed the Ministry of Finance’s cushion, the National Welfare Fund, and continue filling it.

The dependence of Russian economic well-being and the standard of living of the Russian population on oil prices is no secret. Not even for the Kremlin. Back in 2009, President Dmitry Medvedev spoke of “humiliating commodity dependence.” Therefore, it is not surprising that after Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, Western countries began seriously discussing the possibility of imposing an embargo on the purchase of Russian hydrocarbons. A similar ban was imposed on Iran in 2010, so the idea was supported by public opinion in developed countries.

Today, the U.S. president announced an embargo on purchasing Russian hydrocarbons (oil, gas, and petroleum products) and coal (effective from 22 April). The EU has decided to phase out Russian gas by 2030, with a cut of at least half during the year. To my memory, this is the first time that the EU sanctions decision has been tougher on Russia and more painful on the European economy at the same time.

Oil

In my view, the idea of an embargo on Russian oil purchases by Western countries has a minimal material effect on the Russian economy. Most Russian oil is transported for export either by sea or via pipeline to China. The Druzhba pipeline transported 35 million tons (700,000 bar/day) of oil to Europe in 2021, accounting for 14% of total oil exports or 6.7% of all oil produced. The nullification of these exports is not critical for Russian oil companies—the overall reduction in oil production would be comparable to that realized in the spring of 2020 when the world economy faced COVID. A rise in oil prices will obviously offset the financial losses to the Russian economy in this case. At the beginning of this year, the oil price was $77/barrel, and a rise to $88/barrel is sufficient to offset the decline in exports. That said, it is worth recalling that Russia’s 2022 federal budget was planned at a base price of $44/barrel and all tax revenue from a higher oil price was to go to the National Welfare Fund.

It is well understood that once Russian oil is loaded into tankers, it can be shipped anywhere in the world. There is no doubt that at least two major oil importers in the world have not acceded to Western sanctions and would be willing to buy Russian oil. At a substantial discount to the price, as in the case of Iranian crude. We are talking about India and China. Their total oil imports are 713 million tons a year (14.3 mln.barr/day), which means that they will need to switch suppliers for 5% of their oil imports.

In short, a little stress for the oil traders, a few dozen tankers that will have to change the route, and a slight loss for the Russian oil companies from paying for additional transportation services. Not much of a blow to the Russian economy, is it?

Meanwhile, the blowback effect of the ban on the purchase of Russian oil in Europe will be concentrated on two countries: Poland and Germany. This is where the Russian pipeline delivers its oil. Today, these countries have no spare capacity to receive oil brought in by tankers by sea, and building new terminals at a time when oil consumption will start to fall sharply in the next 10-15 years is not a good strategic decision.

Therefore, the EU countries have decided not to give up Russian oil and have made a much stronger decision—to start moving toward rejection of Russian gas imports.

Gas

In recent years, Russian gas exports to Europe (without Turkey) amounted to 150-180 bcm through the pipelines—i.e., 30%-35% of Gazprom’s production. If the European Commission’s decision to cut Russian gas imports by 100 bcm over the year is implemented, Russian oil and gas companies would have to cut production by 13%. If all the cuts came from Gazprom, its production would fall by almost 20%.

Unlike oil, Russian gas has no alternative export options. Gazprom has no liquefaction plants of its own on the Baltic Sea shore (where the pipeline comes in); the design and implementation of such a plant would take years and require imports of European technology and equipment. And Gazprom has no pipelines that could bring gas to China—the power of Siberia does not connect with the main gas fields. However, the capacity of this pipeline is 40 billion cubic meters (bcm), and in 2-3 years, there will be no spare capacity there. Some way out for Gazprom could be the Turkish Stream and the Blue Stream. Their combined capacity is 48.5 bcm, but the Turkish economy does not need much gas.

In addition to the direct effect—reducing gas production—the EU decision will put additional pressure on Gazprom in two ways. First, reducing the volume of gas pumped through the pipelines will increase the unit tariff, the cost of pumping a unit of volume. Second, to pump 55-60 bcm of gas per year to the EU, Gazprom surplus capacity of Nord Stream 1 (which pumped 75 bcm in 2021 and 68 bcm in 2020). At the same time, the agreement signed in 2019 with Ukraine’s Naftogaz envisages a “pump-or-pay” principle for Gazprom, which will have to pay for the transportation of 40 bcm per year until 2024.

The European Commission, in a statement on refusing to import Russian gas, explicitly mentions the main ways to achieve the goal: More intensive use of LNG, a more significant shift to alternative energy sources (which has become much more attractive, given rising gas prices), energy-efficiency measures, and the introduction of compensation for companies hardest hit by rising electricity prices.

War

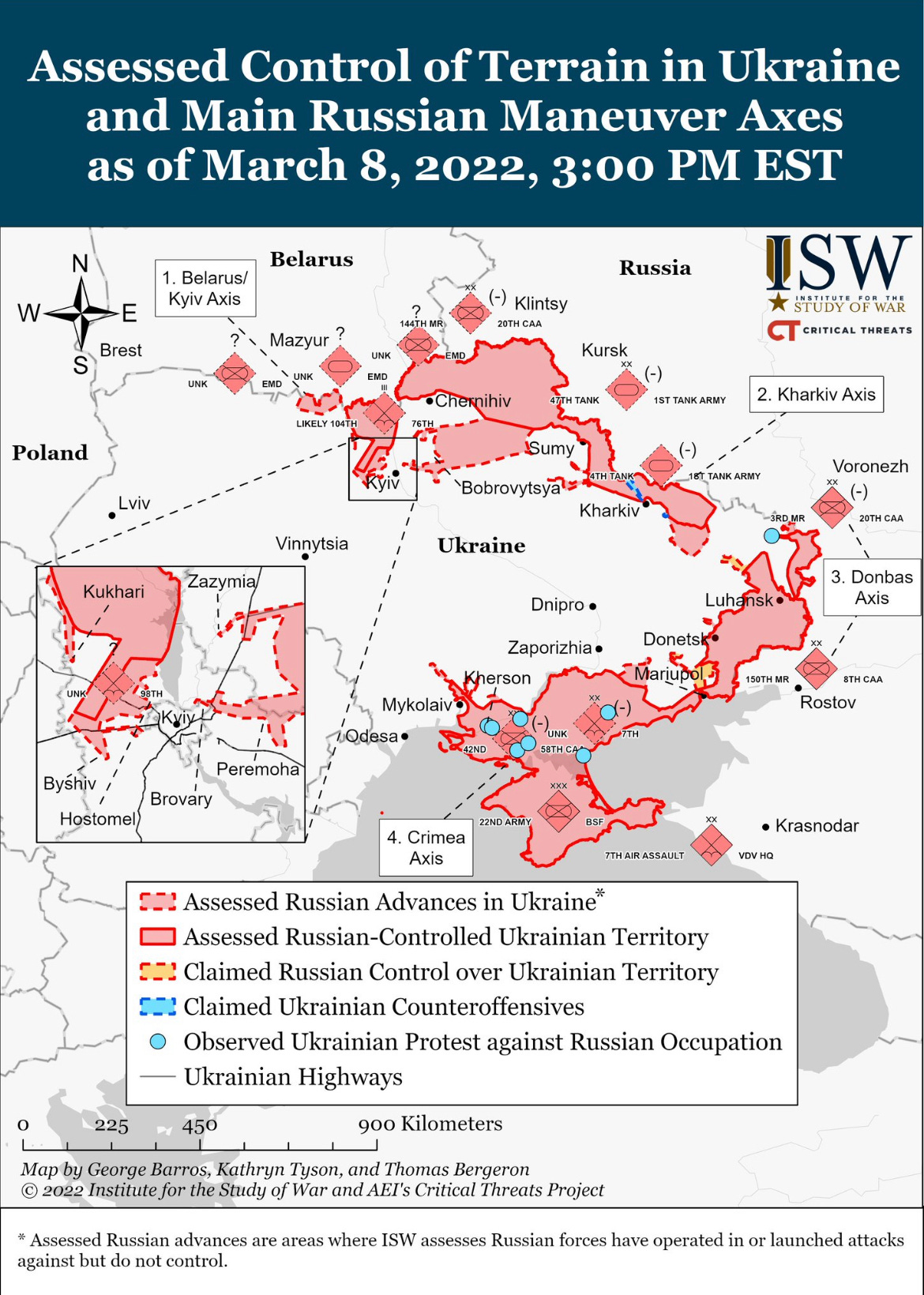

No significant changes.

The backlash

The Russian authorities, once again, are set to spend energy and time devising counter-sanctions, which they believe should hit the economies of countries that have imposed sanctions on Russia. On Tuesday, Vladimir Putin ordered the government to draw up within two days a list of goods whose exports and imports would be restricted, as well as a list of countries that would fall under such restrictions.

To me, this idea seems highly irrational. Russia is a country, 85% of whose exports consist of raw materials or products of their minor processing. On the one hand, most of these goods are sold through traders usually registered in countries that are not significant importers of raw materials. On the other hand, the production of many such commodities is concentrated in a small number of companies, sometimes even in one (e.g., Norilsk Nickel, RUSAL, Phosagro), and introducing an export ban could be excessive for them. My prediction is that an export ban will not work and will only increase transaction costs for Russian companies.

The import ban is painfully reminiscent of the 2014 counter-sanctions when Putin banned food imports to Russia. For various reasons, Russian agriculture failed to occupy the niche it had vacated, which was filled with surrogates or higher prices. Of course, I don’t know which imports will fall under the ban this time, but I am willing to guess that the effect will be very similar.

The very idea of an import ban in a country where 25% of the food market and 50% of the non-food market is filled with imports can work only in an investment-attractive economy or in one that can produce technology itself and create competitive consumer goods. In my mind, the Russian economy falls into neither of these categories.

Incredible foolishness

Apparently, the outflow of foreign currency deposits from Russian banks has exceeded the Bank of Russia’s forecasts and put under question the banks’ ability to meet their obligations.

Today the Bank of Russia has imposed severe restrictions on the use of foreign currency deposits by the public. Until September 9, citizens will be able to withdraw no more than $10,000 from their foreign currency deposits, regardless of the size of the deposit; any withdrawals in excess of this amount will be possible only in rubles.

In addition, during this period, it will be possible to withdraw funds from the foreign currency deposit only in dollars, regardless of the currency of the deposit.

If a new foreign currency deposit is opened, the funds can be withdrawn only in rubles within the period of six months.

The biggest mistake monetary authority may make in Russia is to touch private savings – if there was no bank run until now, it’s going to happen.