UNKNOWN WAR

September 17, 2022

Russian pollsters debate, trying to give the most accurate estimate of the proportion of Russians who support the war the Russian army is waging in Ukraine, as well as to find an explanation for why the numbers are what they are. But I was interested in another question: What kind of war do Russians support? We know from the Levada-Center polls that Russians’ attention to the events in Ukraine is gradually decreasing—over the six months of the war, the share of those who follow the actions closely or somewhat closely has dropped from almost two-thirds to half. But what do Russians know?

There are criminal penalties in Russia for disseminating information about the war that contradicts the official statements of the General Staff. Therefore, on the one hand, pollsters are wittingly afraid to ask such questions directly—the risk that the next day someone will write a denunciation with known consequences is too high. On the other hand, in any case, a considerable part of Russians receives information from the traditional mass media—first, from television programs, which contain plenty of emotions and speculation, but which report little about the actual situation on the front.

Therefore, finding an answer to my questions was not so easy. I had to enlist the help of the Levada Center, which asked three “basic” questions about the course of the war as part of its traditional monthly survey (August 25-31):

Could you say which regions of Ukraine Russian troops are or have been stationed? [1]

Could you say what percentage of Ukrainian territory the Russian army controls?[2]

In your opinion, which statement about the situation in Russian territories bordering Ukraine best describes the situation?[3]

The answers that were received allow me to conclude that Russians’ knowledge of the war is rather superficial: More than a quarter of respondents had difficulty answering the first question, almost a third had a problem answering the second, and variations between different groups of respondents are insignificant.

More than a quarter of respondents (27%) think that Russian troops were present on the territory of not more than two regions of Ukraine; 42% mention three to six. Only 4% of the survey participants named seven to nine regions. Among those who support the Russian military actions, the share of those with “limited” knowledge (from three to six regions) is more significant—45%—against 32% among those who do not support the war. In addition, among opponents of the war, there is a noticeably higher share of those who could not name a single Ukrainian region where the war is going on, about 40%; among supporters of the war, the percentage of the uninformed is just below a quarter (23%).

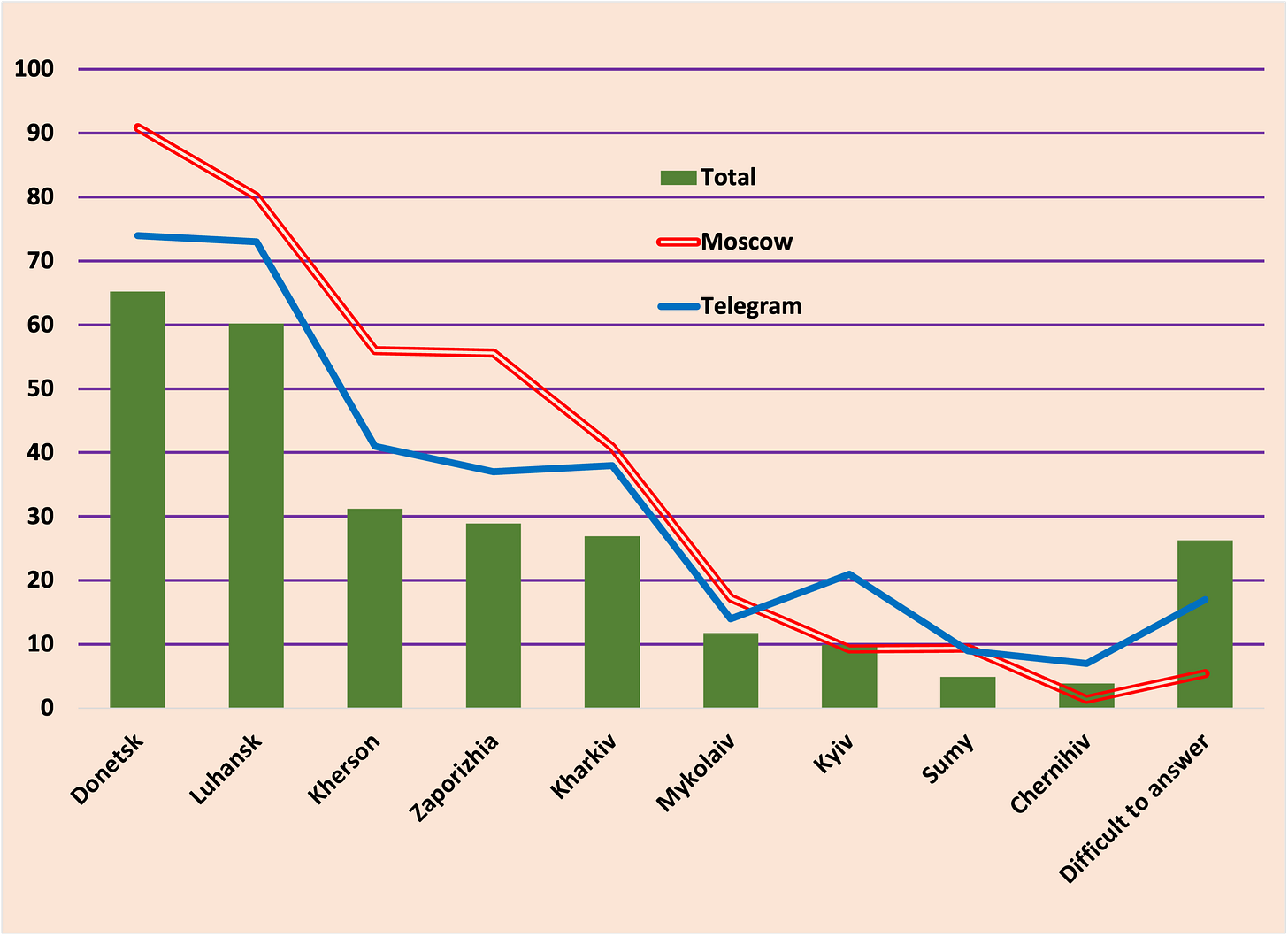

The Russian authorities have named and continue to call the appeal of the self-proclaimed republics, the LNR and DNR, whose independence Russia recognized three days before the war, for help in “liberating the territory occupied by the Ukrainian authorities” as casus belli for the invasion of Ukraine. Vladimir Putin spoke about this in his statement on the night of February 24, announcing the attack on a neighboring country; talk show hosts on state-controlled Russian TV channels constantly remind it. Nevertheless, only 65% of respondents said that the Russian army was present in the Donetsk Region of Ukraine. Even fewer, 60%, named the Luhansk Region.

According to the poll, more than a third of Russians (34%) do not pay much attention to the situation in Ukraine; another 14%, one in seven, do not spend any time on it. In such a situation, it is probably not surprising that the three regions of Ukraine where there have been active hostilities of late—Zaporizhia, Kherson, and Kharkiv—were named by 27%-31% of respondents; 4% to 12% of respondents mentioned the other four regions. The question about the events in Bucha was too dangerous to be asked directly. Still, an indirect confirmation of the fact that not too many people in Russia know about them was the fact that only one in 10 named the Kyiv region.

As I have already noted, there are not many differences among groups of respondents, and they do not allow drawing meaningful conclusions. Perhaps it is not surprising that Moscow residents follow events in Ukraine more closely: 91% of Muscovites who participated in the survey named the Donetsk Region, 80% named the Luhansk Region, and only 5% found it difficult to mention at least one. Another noticeable “deviation from the average” is a higher level of knowledge among those respondents who trust the news received from Telegram channels. Among them, the share of those who named the Kyiv Region is twice as high as the average level.

Analyzing the distribution of answers to the second question about the size of the occupied part of Ukraine, I noted that respondents tend to exaggerate the success of the Russian army: 28% believe that over 30% of the territory is occupied; 39% are “realists,” those who approximately understand the scale of the Russian occupation, indicating the range 10%-20% and 20%-30%; and only 3% believe that it is occupied less than 10%. Almost a third, 31%, had difficulty in answering this question.

The difference in answers was even less significant than in answer to the first question. The most significant number of “realists” is among those who trust TV channels and among residents of Moscow (60% and 54%, respectively); among housewives, jobless respondents, and respondents with “below average” education, there are relatively fewer “realists” (25%-28%) and more of those who find it difficult to answer this question (45%-52%).

Russians, in principle, know the regions-neighbors to Ukraine live a troubled life—only 8% of respondents had difficulty answering. A steady majority (52%) soberly assess the situation, saying that “Russian territory is subject to sporadic shelling.” Slightly more than a quarter of respondents (28%) believe that “the Russian border is reliably protected, the situation is calm.” One in 10 is confident that “Russian territory is subject to constant shelling and attacks.”

Of course, based on three questions, it is impossible to get a clear view of what ideas about the war exist in the minds of the Russians. But here is the main conclusion I made: through a combination of propaganda and censorship the Kremlin has managed to suppress Russians’ interest in what is happening in Ukraine. In some ways, this situation is reminiscent of Germany during World War I: The war was fought outside Germany, and the German population did not see all its horrors. In the fall of 1918, when the German army was on the verge of defeat, it surprised most of the population, including the government, which the military command also kept on meager information rations. But perhaps this is where the analogy ends today. In 1918, the German military shifted the decision to end the war and sign the hard-fought Peace of Versailles to the civilian government. As a result, public confidence in the military even grew, as the popular narrative was “treason by politicians” that led to defeat in the war and humiliation of the nation. Subsequently, the military’s thirst for revenge and Hitler’s insane ideas of world domination led to World War II.

How will Russian society react to Russia’s possible military or political defeat? Whom will it blame for the inevitable decline in living standards? With whom will they pin their hopes for change for the better? We will learn the answers to these questions over time, and the country's future will depend on them.

[1] Correct answer is nine.

[2] Correct answer is 20 percent.

[3] Answer options: a) The Russian border is reliably protected, the situation is calm, b) Russian territory is subjected to sporadic shelling, c) Russian territory is subjected to constant shelling and attacks, and d) Active military operations on Russian territory.