Changes are coming?

August 6, 2023

It is well known that in population surveys, much (if not all) depends on the questions’ wording. Sometimes, by formulating the same question in different ways, obtaining other distributions of responses is possible. In democratic societies, this problem is primarily alleviated by the fact that many companies conduct polls. In a competitive environment, any attempt to tweak the question in such a way as to push the respondent to the “correct” answer becomes evident to the experts, after which the credibility of the results of such a survey drops sharply.

In authoritarian/totalitarian societies, surveys usually are conducted by a very narrow circle of specialists who often must compromise with the authorities and ask questions whose answers can be predicted. Such questions in Russia undoubtedly include questions about support for Vladimir Putin as president or about support for the war (actions of the Russian army in Ukraine). Most respondents (30%-40%) answer these questions positively due to their semi-slavish attitude toward the supreme power—How can we distrust the tsar if we cannot change him? Everything around Ukraine is so ambiguous that it is impossible to understand anything; there is a president for that; let him do what he thinks necessary.

Of course, external solid shocks can change this behavior, seen in the changing level of support for Vladimir Putin. Three times during his almost quarter-century in power, a substantial decline in this indicator has been recorded. The first time, it was triggered by the virtually non-alternative election of 2004 and the Beslan tragedy that occurred shortly afterward; the second time, it was triggered by the severe economic crisis of 2008-09 and the outburst of a powerful protest movement in late 2011-early 2012; the third time, it was started by Putin’s decision to raise the retirement age, which he made immediately after the 2018 election, prior to which he had repeatedly promised not to do so.

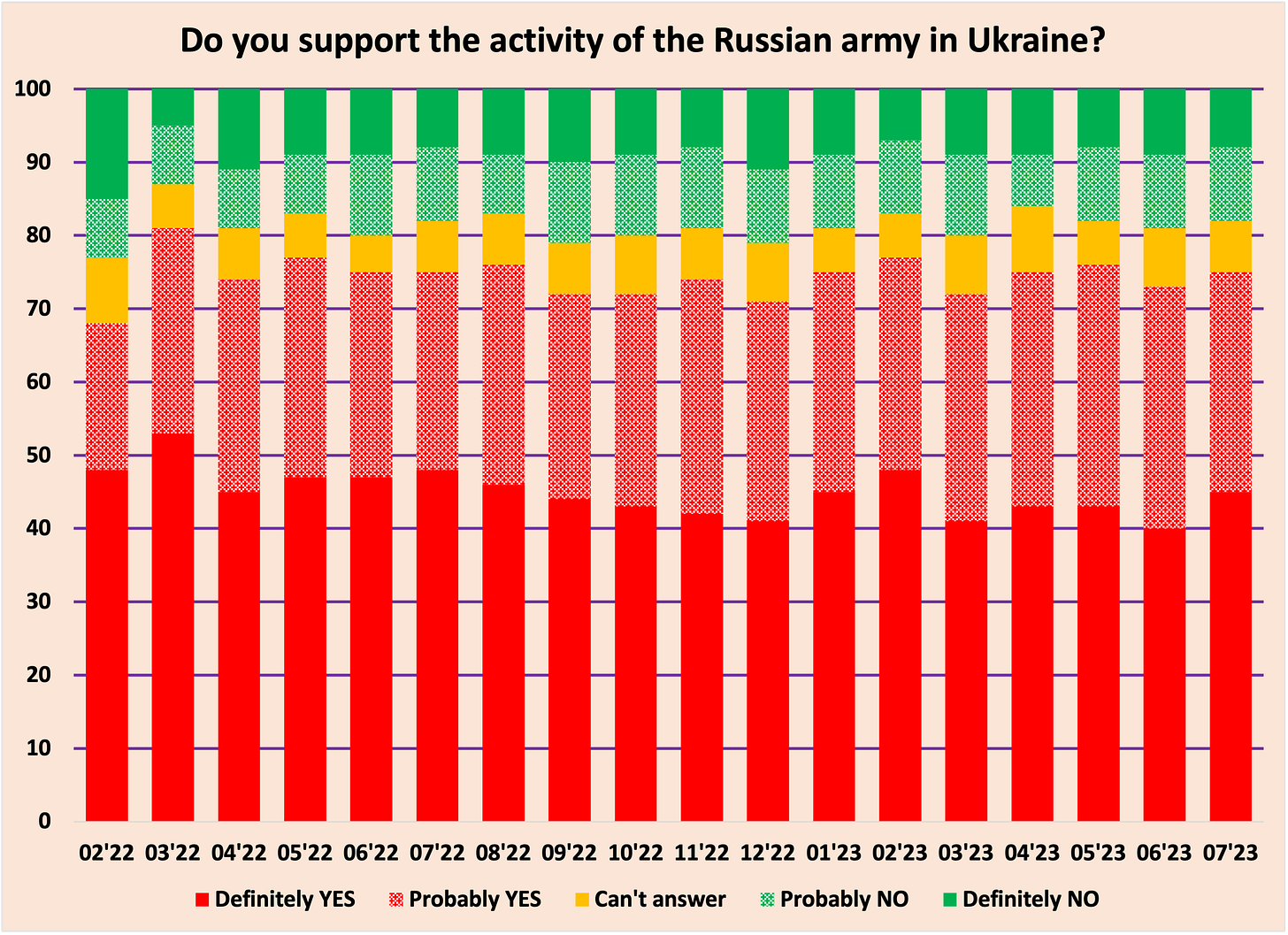

The Russian aggression against Ukraine, which began almost a year and a half ago, has not yet seen similarly strong external impulses (the mobilization of September 2022 did not have a lasting impact on the population), so it should not be surprising that the level of support for the war in various polls remains consistently high.1

Being well aware of the limitations of historical analogies, I nevertheless think it is possible to cite as a “point of reference” the results of polls in the U.S. during the Vietnam War when respondents were asked to answer the question: “Given the events that have occurred since we became involved in the fighting in Vietnam, do you think that the U.S. made a mistake in sending troops to fight in Vietnam?” 2

The graph clearly shows that most Americans did not doubt the success of the “small victorious war.” Although this euphoria quickly evaporated, equality in the answers was formed only after two and a half years of war. By then, the number of American soldiers killed in Vietnam exceeded 25,000.3 Only after more than three years of war did most Americans begin to recognize the beginning of the war as a mistake.4 5

The results of the Levada-Center poll in January-March, when the question was asked in a similar formulation, gave stable results: 23% of respondents were ready to recognize the beginning of the SMO (Special Military Operation) as a mistake, while 66% considered the beginning of the SMO justified. (Six months after the beginning of the war in Vietnam, the results of the poll in the United States were 24%/61%.) This question was not asked of respondents in April and May. After a significant change in the response ratio was recorded in June, it was decided to wait for the results of the next poll to see if the June data was not a random deviation.

The results of the July poll turned out to be very close to those obtained in June, suggesting a shift in public opinion on this issue has begun. The ratio of the answers, 32%/58%, turned out to be comparable to the results obtained in the U.S. a year and a half after the beginning of the war, where the ratio of those who considered the beginning of the war a mistake to those who held the opposite opinion in the polls of September and November 1966 was 33%/50%.

An even more significant shift occurred in assessing how much of a price Russia paid for participating in the SMO. In the surveys at the beginning of the year (January, February, April), when respondents were asked, “Do you agree that Russia is paying too high a price for its participation in the SMO?” the distribution of responses was roughly even between the three groups: One-third of respondents answered “definitely yes,” one-third answered “rather yes,” and another third consisted of those who disagreed with such a statement to varying degrees or found it difficult to answer such a question.

Because no significant dynamics in the answers to this question were recorded, it was decided not to ask it in May and June, and in June to ask it in a different formulation, which implies greater freedom for respondents in choosing the answer options: “What price do you think Russia pays for participation in the SMO?” Even this time, the answers received seemed to require confirmation: 40% of respondents chose the answer ‘very high,’ and 44% chose ‘high.’ At the same time, only 2% chose the answer “low,” and another 1% chose “not noticeable.”

In July, when respondents were asked both questions, half of the respondents (50%) agreed with the statement that Russia is paying too high a price for the war, while the entire increase in this group was due to a decrease in the share of those who disagree with this position; the percentage of those who “rather” agree remained at the level of the beginning of the year—32%.

The results obtained, in my opinion, despite the declared consistently high level of support for the Kremlin’s military adventure, indicate the formation of qualitative shifts in the attitude of Russians to the war. One can confidently assert that this process will continue; economic problems (inflation as real and devaluation as psychological) and the growing number of dead and wounded soldiers will inevitably accelerate it. However, these changes should not be expected to be rapid or occur immediately. The lack of political competition and the intensive work of the propaganda and repressive machine will severely limit Russians’ ability to get information about what is happening in Ukraine and, consequently, slow down changes in public opinion.

Half of Russians (48% in the Levada-Center poll and 49% in the Russian Field poll) believe that the war will last more than a year longer, and this means that most Russians are ready to perceive the war as a new reality in which they will have to live.

For me, the only important conclusion from the answers to such a straightforward question is the dynamics of answers, which does not undergo noticeable fluctuations, and such stability of answers is recorded in polls conducted by different centers. A graph based on Levada Center polls is given to demonstrate the stability of the situation.

The first 3,500 American soldiers arrived in Vietnam in early March 1965; by the year-end, they were 200,000. On February 15, 1973, the U.S. and Vietnam signed an agreement to end the war.

Throughout the Vietnam War, 60,000 U.S. soldiers died, and more than 153,000 were wounded.

The November 2000 poll was conducted by the Pew Research Center.

A quarter of a century after the end of the Vietnam War, more than 20% of Americans disagreed that it was a mistake to start it. It should be noted that this share is in the middle of the range of estimates of the share of core supporters of the war in Ukraine until the victorious end, which is given by different researchers (15%-25%).

It is deeply saddening what's happening out there, hopefully this conflict will find some sort of middle-ground bientot.

Pardonne mon français . . . Je suis obligé d'écrire dans plusieurs langues parce que : 1. La plupart des gens aux États-Unis ont subi un lavage de cerveau leur faisant croire que les Juifs sont leur salut ; et 2., leur anglais est de la merde et ils ne peuvent pas rester silencieux assez longtemps pour entendre ou voir ce qui se passe évidemment autour d'eux.

Le judéo-messianisme répand parmi nous son message empoisonné depuis près de deux mille ans. Les universalismes démocratique et communiste sont plus récents, mais ils n’ont fait que renforcer le vieux récit juif. Ce sont les mêmes idéaux.

Les idéaux transnationaux, transraciaux, transsexuels, transculturels que ces idéologies nous prêchent (au-delà des peuples, des races, des cultures) et qui sont le subsistance quotidienne de nos écoles, dans nos médias, dans notre culture populaire, à nos universités, et sur nos rues, ont fini par réduire notre identité biosymbolique et notre fierté ethnique à leur expression minimale.

L'exil comme punition pour ceux qui prêchent la sédition devrait être rétabli dans le cadre juridique de l'Occident . . . Le judaïsme, le christianisme, et l’islam sont des cultes de mort originaires du Moyen-Orient et totalement étrangers à l’Europe et à ses peuples.

On se demande parfois pourquoi la gauche européenne s’entend si bien avec les musulmans. Pourquoi un mouvement souvent ouvertement antireligieux prend-il le parti d’une religiosité farouche qui semble s’opposer à presque tout ce que la gauche a toujours prétendu défendre ? Une partie de l’explication réside dans le fait que l’Islam et le marxisme ont une racine idéologique commune : le judaïsme.

Don Rumsfeld avait raison lorsqu’il disait : «L’Europe s’est décalé sur son axe», c’est le mauvais côté qui a gagné la Seconde Guerre mondiale, et cela devient chaque jour plus clair . . . Qu’a fait l’OTAN pour défendre l’Europe? Absolument rien . . . Mes ennemis ne sont pas à Moscou, à Damas, à Téhéran, à Riyad ou dans quelque croque-mitaine teutonique éthéré, mes ennemis sont à Washington, Bruxelles et Tel Aviv.

https://cwspangle.substack.com/p/pardonne-mon-francais-va-te-faire