On February 24, Russia began unprovoked military aggression against Ukraine, which continues today. This war has already claimed the lives of thousands of Russian and Ukrainian soldiers and civilians and caused enormous damage to Ukraine’s economy. Western countries have provided and continue to provide limited military and financial aid to Ukraine. Immediately after the invasion, they imposed severe economic sanctions against Russia to stop the aggression. However, the war continues. The Kremlin’s initial plan—a quick seizure of Kyiv and change of power in Ukraine—failed, and the Russian army had to retreat from the Ukrainian capital. But it is more likely correct to speak of a shift in the direction of the main strike by Russian troops rather than the Kremlin’s desire to end the war.

In this situation, many politicians and analysts have begun to ask: Do the sanctions imposed against Russia work? Are they seriously affecting Vladimir Putin’s calculations and assessments and causing him to re-evaluate the situation? Many people recall 2014 when the ruble rapidly devalued after sanctions against Russia were imposed. My short answer is: Yes, the sanctions are working. Moreover, they are working much harder than in 2014, and their effect will intensify in the coming weeks and months, even if Western countries do not impose new sanctions.

Recalling the history

In January 2015, President Barack Obama said that “we were doing the hard work of imposing sanctions along with our allies... Russia is isolated with its economy in tatters.” On the surface, he had reason to believe this: The ruble had fallen 50% since the beginning of 2014, Russia’s currency and financial markets were disorganized, and the Bank of Russia was spending tens of billions of dollars to support the economy.

However, the accurate picture looked somewhat different. Financial sanctions against Russian banks and companies were imposed in late July, and early August 2014 after militants shot down Malaysian Boeing MH-17. The collapse of the Russian financial market happened four months later in December. At the very least, this means that the sanctions were not instantaneous. But two other factors should not be forgotten.

In February 2013. Vladimir Putin decided to appoint Elvira Nabiullina, who at the time had no experience in government agencies responsible for macroeconomic policy (the Central Bank or the Ministry of Finance), to the position of Chairman of the Bank of Russia.1 Nabiullina defined her main objective in the new position as maintaining the stability of the ruble exchange rate, which, in her opinion, should curb the growth of inflation, and decided to conduct currency interventions to this end. During the first eight months of her work, the Bank of Russia spent $25 billion. In principle, the amount is not very large—only 5% of Russia’s total international reserves or 7% of the Central Bank’s reserves (excluding the Reserve Fund and the National Welfare Fund). However, constant interventions and the achievement of the set goal—maintaining the stability of the ruble exchange rate—have led to two significant consequences. On the one hand, the economy has accumulated the potential for disequilibrium between supply and demand for currency. On the other hand, Nabiullina’s team believed in the correctness of its policy.

The annexation of Crimea and the changed sentiments of Russian business did not force the Bank of Russia to change its tactics. The sanctions imposed by the U.S. and the EU did not affect the financial sector (they were levied against small banks controlled by Putin’s friends) but provoked capital outflow from Russia. In this situation, Nabiullina again considered maintaining the stability of the ruble exchange rate to be her primary task, and the Bank of Russia continued its currency interventions. From the beginning of March until the end of July 2014, the ruble-dollar exchange rate remained stable, and the volume of foreign exchange interventions amounted to an additional $25 billion.

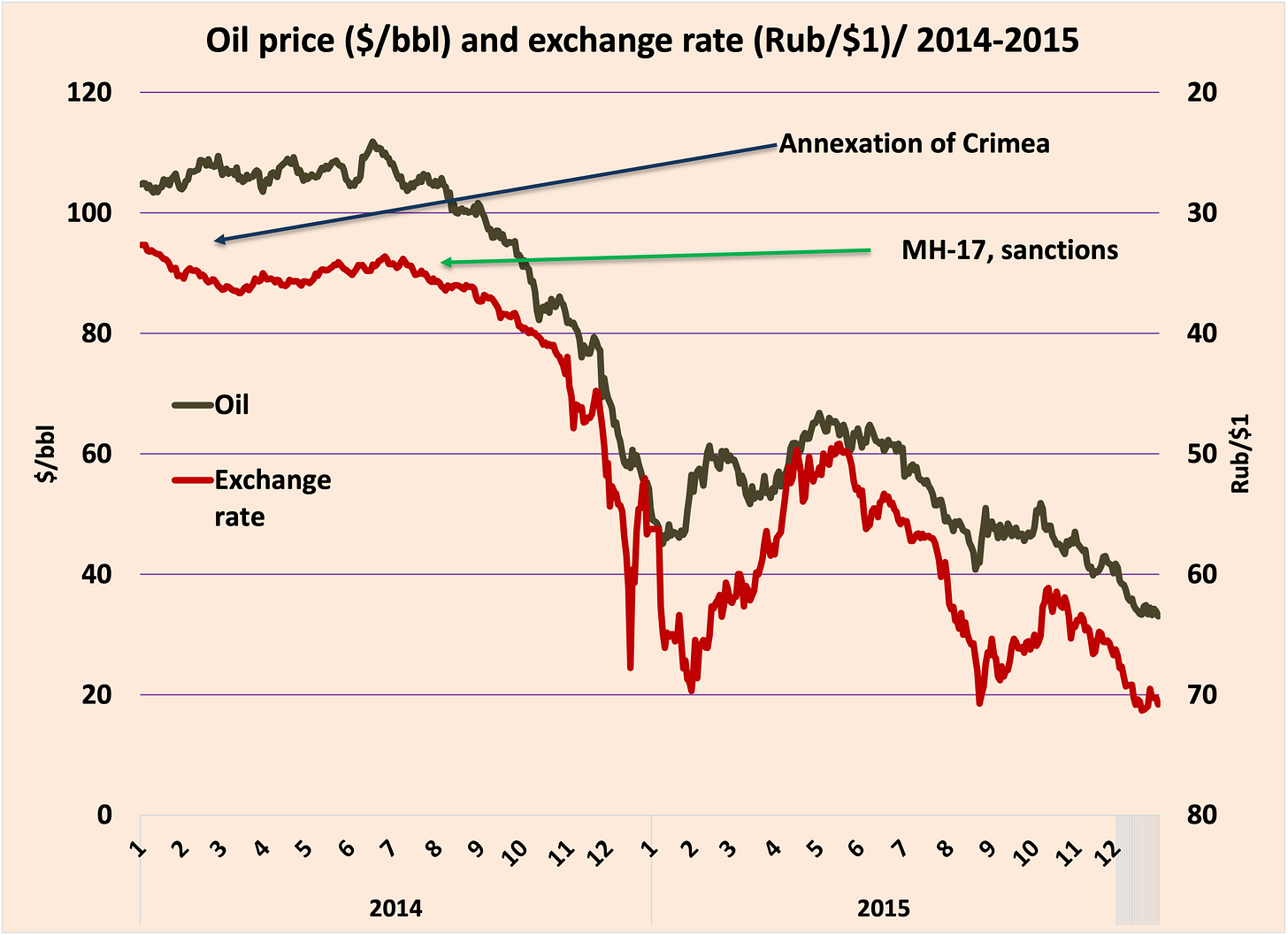

The situation in the Russian economy began to change rapidly in mid-August 2014 when global oil prices began to decline: From $105/barrel in early August, they fell to $92 by the end of September and to $50 by the end of December 2014. The Russian economy is always sensitive to this indicator. The lessons of the 1998 and 2008 crises have formed a stable stereotype of behavior among Russian banks: Oil is getting cheaper, so the dollar will get more expensive, and one should buy it. To buy dollars, you need rubles, which the Bank of Russia quietly issued to banks on the security of securities or currency purchased from the Central Bank. At the same time, the ruble was gradually devaluing, which made such operations highly profitable to the banks: Receiving rubles at 10% per annum, they bought dollars, which rose in price at an annualized rate of dozens of thousands of percent.2

Nabiullina’s team persisted until mid-December when the Russian market was hit hard by the sanctions imposed in July and August. For several years, Russian banks and companies were active borrowers in the foreign capital market, steadily recovering from the 2008/09 crisis. The standard practice for Russian borrowers was to refinance old debts by taking out new loans or by offering their shares. But this mechanism stopped working after the U.S. and the EU banned access to their capital markets formally for the top 10 Russian borrowers, but in fact, the ban applied to all Russian banks and companies.

And then, it turned out that the last quarter of 2014 and the first quarter of 2015 were the peak periods for repayment of foreign debts, which totaled about 5% of GDP. To repay their debts, exporting companies began to accumulate foreign currency reserves and thus reduce sales of foreign currency in the market. In contrast, other companies and banks began to buy foreign currency intensively, which increased the demand for it. It was clear that such a situation was not sustainable.

The explosion happened in mid-December when Russia’s largest oil company, Rosneft, could not find the money to repay its foreign loans. The Bank of Russia provided it with the necessary funds in a highly dubious transaction.3 This transaction became known to the market and provoked panic—the demand for currency jumped sharply. In this situation, the Bank of Russia realized the futility of its efforts and took the only right decision: It raised its interest rate from 10% to 17%, making ruble loans more expensive for banks, and at the same time abandoned the tactics of supporting the ruble—in one day the dollar rose by 11% after it had risen by 20% over the previous two weeks. The measures taken led to the fact that the situation in the foreign exchange market began to normalize gradually.4 Although the USD exchange rate continued to fluctuate sharply throughout January, the ruble began to strengthen progressively from the beginning of February. By the beginning of May, its appreciation had reached 40%.

But, of course, it would be a mistake to believe that the normalization of the financial market in Russia happened solely due to the actions of the Central Bank—since the low in mid-January 2015 ($45), oil prices began to rise rapidly, and by the end of the month, they exceeded $56 (i.e., rose by a quarter).

Thus, the financial crisis of December 2014 in Russia was a combination of four factors: Falling oil prices, peak payments on foreign debt, sanctions, and erroneous policy of the Bank of Russia.

The destabilization of the financial market and the ruble’s devaluation certainly impacted the real economy, but this impact was not too strong. First, the Russian financial market is at the initial stage of its development, and its role as an intermediary in the redistribution of capital is weak. Large institutional investors (insurance and pension funds), which are supposed to accumulate savings and transform them into investments in the national economy, have not yet formed in Russia. In addition, in the fall of 2013, the government and the Bank of Russia launched a reform of pension funds, which halted their operation in 2014-2015. 5

Second, the sectoral sanctions imposed on Russian companies in 2014 were not very significant: They affected the military-industrial complex and a few small oil and gas fields. The effect of these sanctions is statistically insignificant, and they can be neglected for analytical purposes.

A much more severe impact on the economic situation in Russia in 2014-2015 was caused by the counter-sanctions—the August 2014 ban on food imports from countries that joined the sanctions against Russia (what are now called “unfriendly countries”) imposed by Vladimir Putin. This decision was made without prior discussion or preparation and went into effect immediately after publication. The main result of this decision was a reduction in the supply of food products on the market and, consequently, an increase in food prices.

In mid-2014, imports accounted for more than a third of the total supply in the food market and more than 50% in the non-food market. The devaluation of the ruble during the second half of 2014 and early 2015 pushed up prices; inflation peaked in January 2015, when prices rose by 3.85% during the month. After that, the inflation rate began to decline, and as early as April, the rate of price growth fell below the pre-crisis level of 0.5% per month.

The fall in GDP began in late summer 2014 and continued until late 2015, and it was not very severe—2.3%. After that, the Russian economy stagnated for another year; it reached pre-crisis levels in the fall of 2017, but up until the end of 2020, the growth rate was very sluggish—relative to mid-2014, Russian GDP was only 2.7% higher.

The dynamics of industrial production essentially repeated the dynamics of GDP. However, the decline in the industry was shorter and less deep: It began only in January 2015 and ended in mid-summer of the same year, with the fall not exceeding 2.5%. By the end of 2020, the total volume of industrial production was more than 10% higher than mid-2014.

To sum up the historical overview: The sanctions imposed on Russia in July-August 2014 had a substantial impact on the financial sector, but their effect was amplified by other objective (oil price) and subjective (Bank of Russia policy) factors. In addition, the start of these sanctions coincided with the period of peak payments of Russian banks and companies on foreign debt, which intensified their effect. The strongest manifestations of crisis phenomena in the financial sector of Russia were observed in early 2015 (five to six months after the imposition of sanctions); the effect of sanctions on the real sector of the Russian economy was not very significant in the short term (a drop in the economy) but very noticeable in the medium term. If the Russian economy grew at an average rate of 3% per year from 2014 to 2020, it would be 20% larger by early 2021.

Nabiullina spent eight years in the Ministry of Economy (First Deputy Minister in 2000-2003, and Minister in 2007-2012), but this agency deals with regulatory issues in Russia.

This is called “compounded percent”: 1% daily growth equals 3,678%, assuming this growth continues 365 days in a row.

Otkritie Bank received a loan of 600 billion rubles ($15 billion) from the Bank of Russia, secured by Russian Eurobonds from its portfolio, and loaned this money to Rosneft, which bought the currency from the Bank of Russia. The Bank of Russia took the securities as collateral at an inflated valuation and did not demand that Otkritie increase the collateral when the price of the bonds fell.

In addition to raising the interest rate, the Bank of Russia introduced loans in foreign currency to Russian banks, which reduced the demand on the exchange, where the ruble exchange rate is formed. This tool played an important role in calming public opinion: Although the Bank of Russia gave part of its foreign currency assets to banks, it did not reflect this in the dynamics of its foreign currency reserves.

Moreover, by continuing this reform, the government later actually eliminated the system of mandatory pension savings, which dealt an additional blow to the financial market. The system of large pension savings in Russia has not yet been restored.