Three Months Under Sanctions. And what?

Weekend essay, May 21, 2022

Strong or weak?

Two big surprises

What does the Kremlin see?

What to expect?

Strong or weak?

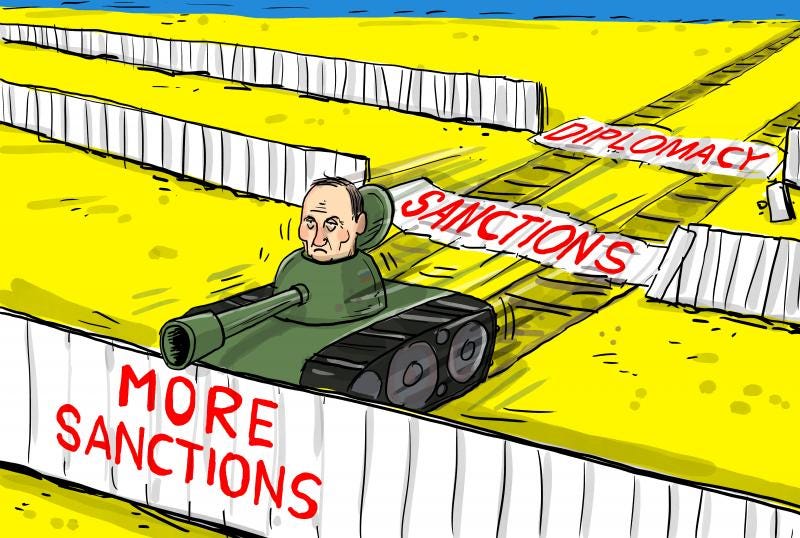

The effect of the sanctions imposed after the Russian invasion of Ukraine was much more robust and manifested itself much faster than was the case in 2014. But sanctions didn’t stop the war and will not stop the war.

The sanctions imposed in late July and early August 2014 (after the downed MH-17) were focused on the financial sector (closing the capital markets), accompanied by a rapid drop in oil prices (almost halved from July 1 to December 31); the erroneous policy of the Bank of Russia, which until mid-December had unlimited loans to banks in rubles and sold currency to maintain the ruble rate; and the ruble devaluation associated with these two factors. As a result, consumer inflation accelerated to less than 4% per month in January 2015. A gradual increase in global oil prices and the Bank of Russia’s transition to a floating ruble exchange rate in spring 2015 sharply reduced inflationary pressure. A change in the U.S. administration’s position restored the Russian economy’s access to global financial markets in mid-2016.

The 2014 sanctions in the real sector were not significant: The ban on U.S. and European companies from cooperating in offshore oil projects (seven such projects) plus export restrictions for the military-industrial complex. As a result, the economy’s contraction was not significant (2%), but this should be added to meager growth rates in subsequent years (2% on average per year for 2016-2019, excluding the impact of COVID). Thus, the cumulative effect of the 2014 sanctions can be estimated as the difference between the actual growth rate of the Russian economy from 2014-to 2021 and the potential 3% growth rate1—without the sanctions, Russia’s GDP in 2021 would be 16% higher than in reality.

After the sanctions were imposed in 2022, inflation accelerated to 10% per month almost overnight, and the ruble fell 40% in two weeks with rising oil prices. Forecasts of the Ministry of Economy and the Bank of Russia predict a 10% drop in the economy by the end of the year, but given the growth of January-February, more revealing is the estimate of the fall of the 4th quarter of 2022 compared to the same quarter of 2021: 13%-15% in the forecast of the Bank of Russia.2 Even non-specialists in macroeconomics can see the difference in scale.

Two big surprises

The big surprise for me was how easily and effortlessly the Russian authorities solved the problem related to the freezing of the Bank of Russia assets—an almost complete ban on capital transactions and a ban on many current transactions reduced the effect of this measure to virtually zero. With a solid current account surplus, the Bank of Russia does not need the accumulated foreign currency reserves: A significant excess supply of currency over its demand allows the public to demonstrate that the authorities and the economy can withstand the sanctions and minimize their impact. At the same time, the Ministry of Finance has no problems with buying foreign currency for the needs of current budget expenditures, and the Bank of Russia can issue metered permits to purchase foreign exchange for banks and companies to make payments of a capital nature.

Of course, this decision, having allowed solving the tactical problem of stabilizing the financial market, entails serious issues, the severity of which will increase over time—the actual inconvertibility and multiplicity of the ruble exchange rate, the lack of clear rules of access to purchase currency will press economic activity and lead to irrational decisions. But this will be the problem of the Ministry of Economy, and it is unlikely that the Bank of Russia will dare to loosen its grip for the sake of the interests of another agency.

The second surprise, which had a powerful impact on the Russian economy, was the “moral sanctions” and foreign companies’ temporary or permanent refusal to work in Russia and with Russia. The strongest impression was caused by the departure of BP, Shell, Renault, Carlsberg, McDonald’s, Heineken, and Société Générale, which admitted multibillion losses; the shutdown of numerous companies selling consumer goods; and the Hollywood movie companies. But from the point of view of the effect on the real economy, the most significant were the blockade of Russia by container shipping companies and the refusal of global oil traders to work with Russian oil.

What does the Kremlin see?

If we look at the West’s sanctions policy, standing in the Kremlin’s shoes, we can see the following.

First, there is no complete unity despite talk of unity in the West. The U.S. and the European Union independently form lists of people, banks, and companies subject to sanctions. The most profound difference is the attitude toward Sberbank, which is not allowed to work in dollars but is allowed to work in euros. In the end, there were no intractable problems for the bank or its clients.

Second, the West seems to have exhausted the potential for imposing new sanctions. The inability of the European Union to agree on the sixth package of sanctions suggests that the reverse effect of their imposition on the EU economy may exceed the direct impact on the Russian economy.

Third, the West does not want to break off all relations with Putin’s entourage or with Russian business. Proof of this can be seen in the loopholes left in the imposition of personal sanctions. Most of the relatives of the “Putin hundred” members remain outside the sanctions. In addition, the West looks quite calmly at the transfer of assets to unknown persons immediately after the sanctions are announced, using agreements with a bygone date.

What to expect?

I disagree with the way the Bank of Russia experts have shown the trajectory of the Russian economy’s contraction—a strong decline in the second quarter and its deceleration toward the end of the year. In my opinion, it could be quite opposite: I do not expect to see any significant qualitative changes in the state of the economy in the next month or two. Until the end of summer, the economy will be “accumulating the potential for a freefall”—depletion of stocks, the disappearance of suppliers, inoperability of supply chains—all of this can, to a minor extent, affect the rate of fall and create the illusion that everything is not so terrible. The acceleration of the decline at the end of the year may come as a surprise to the Kremlin.

The most serious challenge is the drop in imports, which, according to The Economist, amounted to 44% in April. This means that in two to three months, the supply squeeze will reach the corporate sector and the population. The fastest consequence will be a decline in the supply of consumer goods, which will inevitably translate into higher prices. In the medium term, the reduction in imports of intermediate goods will break the technological chains and intensify the economy’s decline. However, I do not see what the authorities can do to overcome this threat—the main burden will fall on companies that will fight for survival.

The second challenge, which is already visible to everyone, and to which we will have to respond, is the strengthening of the ruble. Without easing the current exchange restrictions, the ruble has considerable potential for further strengthening, which should worry the Ministry of Finance. It will lead not only to a decrease in current income but also a decrease in the size of the National Welfare Fund in ruble terms. Considering that a large part of the restrictions is based on political motives—restrictions on banks, companies, and individuals from “unfriendly countries,” which are the main counterparties in capital transactions—I am not ready to try to guess how the Bank of Russia will extricate itself from the current situation.

The third short-term challenge facing the authorities is the need to decide on the level of indexation of pensions and public sector wages this year. The projected inflation rate for this year exceeds 20%, and because a spike in inflation occurred in the first quarter, the drop in the actual level of pensions and public sector wages could be very severe. On the one hand, the Ministry of Finance has sufficient reserves for indexation. Still, on the other hand, the Ministry of Finance has complete uncertainty about budget revenues, which could collapse if the oil embargo proves harsh and works. With the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Economy starting to prepare the 2023 budget as early as June, the cost of indexation could become significant for the treasury.

This is somewhat lower than the growth of the global economy over these years - thus, I tried to take into account the effect of collapsing oil prices in 2014-2015.

I am cautious about any forecasts made so far - too little statistical data is available to experts, and all forecasts are based on numerous hypotheses, whose viability can only be tested with time.